[This is the written form of my presentation What’s Your Problem? Putting Purpose Back into Your Projects]

Our story begins in the 1980s at Procter & Gamble, the largest consumer goods company in the world. They make Bounty, and Mister Clean, and Dawn and lots of other brands you know and love. P&G was raking in the dough. But they had a problem: they needed a new floor cleaner.

So they turned to the smartest people they know — their chemists — to come up with a better soap for mopping floors. P&G employs more PhDs than any other company in the world. Surely those PhDs could solve the problem.

But the stronger soaps the chemists created were stripping the sheen from floors and irritating people’s skin. Ouch. That would be a PR nightmare. So they went back to the drawing board, again and again and again.

After years of prototypes and failed efforts by their chemists, P&G finally decided to bring in a different group of experts to find a solution: Designers.

P&G hired the designers at Continuum, an industrial design firm based in Boston, with offices around the world. The folks at Continuum realized that they were never going to come up with a better cleaning solution than the chemists could, so they had to take a different approach.

They went to people’s homes to watch them mop their floors. Something the chemists had never done.

What they learned is that mopping is actually really messy. Filling the bucket with water and soap, wetting the floor, wringing the mop, and worst of all, sloshing the dirt back onto the floor in the process. Gross. Not to mention once you’re done — spilling out the dirty water, rinsing off the mop in the bathtub, cleaning up the bathtub. What a chore!

The researchers easily saw the truth: The issue wasn’t the strength of the floor cleaner after all; the whole process sucked.

Then at one of their home observations, an older woman spilled her coffee in the kitchen (though rumor has it one of the researchers spilled it on purpose). She got some paper towel, wet it under the faucet, and bent down to wipe up the spill.

And with that…the Swiffer was born. A wet paper towel at the end of a stick.

No one needed a stronger cleaning solution. P&G had misunderstood the problem and the chemists had never taken the time to understand it.

With the Swiffer, there’s no water needed. No big mess. Nothing else to clean afterwards. It just works. I’m completely obsessed with mine, aren’t you?

The numbers say you are. In its first four months on the market, the Swiffer generated $100 million in sales. 11.1 million Swiffer starter kits were sold in the first year. Swiffer is now P&G’s second most popular consumer product, with annual sales of $500 million. The 2nd most popular product of the world’s largest consumer packaged goods company?! I’d say that’s legitimate success.

So what’s the lesson here? Design is problem solving.

Design is both problem and solution. In order to know we are creating the right solution, we have to make sure we’re solving the right problem.

It’s amazing how often this reality is ignored. Companies invent for the sake of invention without caring, understanding or appreciating the problems their customers actually face. And this is the problem I’m trying to solve: obliterating this nonsensical behavior from business practice.

As a consultant, I work every day to help companies establish a meaningful, purposeful approach to solving their customers’ real problems. I do this by relying on three principles of problem solving:

- Process: Define the problem before trying to solve it.

- People: Ask questions to root out the truth.

- Purpose: Be obsessed with the problem, not the solution.

Following these principles is the difference between being strategic versus just being tactical. And when you shift to being a strategic thinker, you start to have a much greater impact on your organization and your customer.

I can’t do this alone. I need your help. We can only make a widespread and permanent change to the role businesses play in customers’ lives if we band together and agree to do things differently.

I will go into each one of my principles in the hope that my methods are useful to you in furthering your own mission.

Process: Define the problem before trying to solve it

Albert Einstein said, “If I had one hour to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem and 5 minutes finding the solution.”

The more time we spend unearthing what the problem really is, the better positioned we are to solve it.

The first time I saw just how powerful this can be was on a project with Happy Cog a few years ago. Jeffrey Zeldman kindly asked me to be the user experience designer on a project for Brighter Planet, a company that is dedicated to giving people ways to help fight global warming.

At the time, their business consisted only of this credit card:

Instead of getting airline miles or cash back, each purchase on a Brighter Planet credit card goes towards carbon offsets, helping fund renewable energy projects across the United States. Needless to say, this was a credit card that only an environmentally conscious person would want to have.

Meanwhile, the Brighter Planet scientists had been working on a very powerful way to accurately calculate a person’s carbon footprint based on a variety of behaviors like what you eat, what you drive, where you live, etc. They really felt like they’d created something groundbreaking. But the calculation required pages of questions and took forever to complete.

The reason they had reached out to Happy Cog was because they wanted to create a social network for people to learn and track their carbon footprint, and then share it with their friends. They saw their target audience as being people they called “Deep Greens” (a.k.a. tree-huggers). The type of people who’d spend half an hour online to calculate their carbon footprint.

We needed to learn everything about them we possibly could.

Problem Setting > Solving

Before we asked “how do we build?” we asked “what is the right thing to build?” Problem setting must proceed problem solving in order to ensure you aren’t solving the wrong problem.

How do you know if you’re solving the wrong problem? Well first let’s make sure we’re all clear on this: What is a problem in the first place?

- A gap between the current state and the desired state, AND

- The problem owner wants to do something about it

In order for it to be a problem, both of these bullet points have to be fulfilled. If there isn’t a gap between the way things are the way they should be, it’s not a problem. If there’s a gap but the person for whom the gap exists doesn’t want to narrow it, it’s not a problem. Not everything we see as a problem is actually a problem. We don’t get to decide. Most of us aren’t making products for ourselves; we’re making them for our customers and for our clients. So make sure the problem you think you have passes this test before you move forward.

That’s what we had to do on the Brighter Planet project. The first thing we did was talk to a few people who considered themselves to be passionate about environmental consciousness. We asked them about their lifestyles. We asked them about their values. We asked them about calculating their carbon footprint. We wanted to figure out what challenges they face in their lives and how this site could help them.

We learned a few very interesting things. Some things we never expected to hear. Some things we had never heard before.

Some people are so dedicated to conserving water that they turn the shower off when they’re soaping up. Others wait until everyone in the office leaves so they can change the lightbulbs to save energy without anyone finding out. But one thing was for sure: tree-huggers did not need to calculate their carbon footprint. Nor did they need yet another place to get tips for how to lower it. They subscribe to every website on the topic, belong to every community, are the go-to people in their circle of friends on how to live a more eco-conscious life. They are very well informed.

There just wasn’t a problem there.

We knew that Brighter planet had the wrong target audience in mind. It wasn’t “deep greens.” But who was it? One of their ad campaigns on mommy blogs had done really well, so we decided to talk to a few mommy bloggers to better understand how they viewed eco-consciousness. This was a fact-finding mission. We needed to understand what the relevance was there.

And that brings us to my second principle of problem solving:

People: Ask questions to root out the truth

If we don’t take the time to learn about the people we serve, we’ll never end up creating a solution that really makes their problems go away. We’ll just be creating a bandaid that will eventually stop working.

The problem is out there, not at your desk.

I made a promise to myself a couple years ago that I would spend as little time on the computer as humanly possible. Instead I dedicate my time to meeting people face to face, spending time with my clients and teammates, getting to know their customers and prospects, learning more about the world, traveling more, leaving my comfort zone.

I realized the pain of the problem is out there, and I’m not going to understand it any better sitting here. I now see myself as an anthropologist more than anything else. And discoveries don’t happen without a change of perspective. You need to get out into the world your users live in in order to truly understand them.

There are many different types of user research and they’re all designed to get to the root of the problem:

- Interviews

- Observations

- Surveys

- Card sorts

- Diary studies

- Etc.

My preferred methods are one-on-one interviews, and observations whenever I can.

Sometimes an organization will say they’ve already done a ton of research with users; the marketing department has personas. Then the challenge becomes helping them to understand the difference between market research and user research.

Market research tends to look like the photo on the left: a group of participants sitting around a table with a moderator facilitating a discussion while some unknown stakeholders observe behind a one-way mirror. These discussions tend to result in groupthink, where the most outgoing participant dominates the conversation and varying perspectives are suppressed.

User research tends to look more like the photo on the right: an interviewer focused on one participant at a time, having an intimate conversation, building a rapport. These discussions tend to result in richer data and a deeper empathy for the participant.

- Market research –> what people like

- User research –> what people do

Market research is an effort to discover people’s opinions, likes and dislikes. User research is an effort to discover people’s behaviors and needs, motivations and attitudes, and most of all frustrations.

Great design improves the way people do things, that’s why knowing what people do beforehand is critical. In order to truly understand our target audiences’ problems, we need to know more than what their views are; we need to discover why they hold those views and how it impacts their actions.

Conducting User Interviews

When it comes to conducting user interviews, there are a few things you can do to ensure you squeeze out every last drop of awesomeness from your participants. In a blog post titled, My Best Advice for Conducting User Interviews, I go into depth on the 10 following tips (plus a few more):

- Set the schedule yourself

- Be casual and conversational

- Ask open-ended questions

- Ask the question, then pause

- Ask about behaviors, not feelings

- Play dumb

- Don’t judge their answers

- Paraphrase what you heard

- If you’re wondering, ask

- Be grateful

Now the question is: what are you going to ask?

I craft a set of questions for each project that I do. Questions aren’t really reusable from one project to the next, but I follow a certain format and ask a certain type of question. I’ll take you through the ones I used for Brighter Planet.

Lifestyle Questions

- Tell me a bit about yourself. Where do you live? Where are you from? What do you do?

- What kind of home do you live in? What do you use for transportation? What kind of special diet do you have, if any?

The lifestyle questions are the easiest for participants to answer; they are questions they’re used to getting asked. This allows you to establish a nice back-and-forth with the participant that isn’t strained. You’re easing them into the conversation, not jumping down their throat with the toughies right off the bat.

Context Questions

- How did you become eco-conscious? How long has it been?

- How do you conserve? Since when?

- What are the obstacles in your life that prevent you from conserving more?

- What is the value of being eco-conscious?

The context questions help you to get a sense of your participant’s perspective on the topic at hand, where they fit into the broader ecosystem. The information around the information you’re digging for, to give it greater meaning.

Influence Questions

- Where do you get your information on environmental issues/conserving?

- What eco-conscious or environmental sites/blogs/publications do you read?

- What environmental organizations do you belong to? Why those? How did you hear about them?

Influence questions get at the participant’s sources of information. What is their perspective being shaped by? What impact is it having on their behavior? These are the inputs they’re taking in on a regular basis that are affecting who they are and how they see the world.

Social Questions

- With whom do you share environmental info that you find? How?

- Tell me about a recent conversation you’ve had with a friend or family member about the environment or “going green”

- What do you think is preventing your friends or family from doing more?

Social questions are the flip-side of influence questions. Who are they sharing information with? How is what they have to share shaping other people’s lives? How do relationships impact this area of their lives or work? This all helps to identify how you may need to facilitate these social connections within your system.

Familiarity Questions

- What do you know about carbon offsets? Have you purchased them?

- Have you calculated your carbon footprint? Where? How?

In all of the previous questions, you may have noticed that I haven’t really asked about Brighter Planet at all. In fact in all of my interviews, I rarely ask anything about the organization themselves. I’m trying to get to know the person as a human being, not as a user.

But the familiarity questions give me a chance to more directly address the solution that my client has already proposed. Does a solution like this already exist in their lives and how has it impacted them?

These are the only non-open-ended questions I ask. Have you…? Do you…? These result only in Yes or No answers. All other questions I ask in my interviews are open-ended Who, What, Where, When, Why, How, How Much, How Often, etc. When I need to directly ask them whether or not they do something, I use a little trick. I ask, “To what extent do you…” That forces them to give a more in-depth answer than just Yes or No.

Web Use Questions

- What other websites do you frequent?

- What social networking sites do you use? Why these?

- How often? How many friends/followers?

- What do you do most often on each site? What was the last thing you did on ?

Tech Use Questions

- What kind of computer do you own? When did you buy it? Who else uses it?

- How do you connect to the Internet?

- What kind of mobile phone do you have? When did you buy it? What do you use it for?

- What other devices do you own?

Both the web and tech questions help me to understand how the client’s potential solution fits into their broader digital world. Their level of engagement online and their technical savviness are constraints we need to work within. If we assume what sites they visit and what devices they own, we’ll end up creating a product they likely won’t use.

Synthesizing User Interviews

I asked all of these questions, and I have all these notes. Now I have to make sense of everything I heard.

I go through my scores of notes and I write down every statement I heard, one at a time, into one of the following six categories: Background; Attitudes; Behaviors; Motivations; Frustrations; and Tech Use. Background is any historical or circumstantial information that gives the person some context. Attitudes are how they feel about things. Behaviors are what they do. Motivations are why they do them. Frustrations are what they wish they could be doing. And tech use is what technology they use, how they use it, and how savvy they are about it.

Every statement fits into only one category. It never fails. So I write them down, one by one.

Each time I happen upon a statement that’s the same as one I’ve previously written, I put a tally mark next to it. As I go through each subsequent interview, I begin to see the trends among them, and the most common behaviors, attitudes, motivations and frustrations emerge.

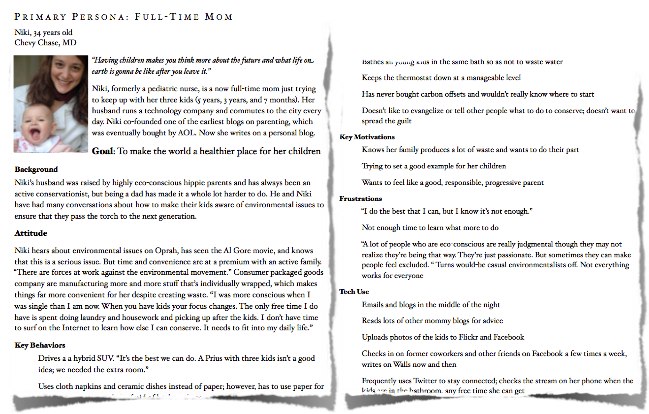

Once I’m done synthesizing all of my notes, I document my findings in a set of personas. The personas document allows you to create a profile of your users to share with other members of your team and repeatedly refer back to when making important design decisions. [More on my thoughts on the value of personas.]

I put demographics and a photo so that they are easier for me, my teammates and my stakeholders to empathize with. But I’m not segmenting users demographically; I’m segmenting them psychographically. That means I’m classifying people according to their attitudes, their aspirations. Psychological criteria, not demographic.

When you see trends in behavior, you know you have a segment. When you see divergent behaviors or motivations, you have another segment. It takes some practice to be able to spot the trends effectively, so take your time and bring in a colleague to comb through the notes with you.

On the Brighter Planet project, we learned quite a bit from our interviews with mommy bloggers.

- Impractical advice: Cloth diapers are more eco-friendly than disposable diapers, but most moms simply can’t bear to use them out of the house. The pain of carrying around dirty cloth diapers outweighs the benefit to the planet.

- Guilt trips: Moms feel guilty that they aren’t doing enough and hate being pressured by other moms who seem to do more.

- And most interestingly to me…One-handed browsing: the only time moms of infants get to sit at the computer and check Facebook…is when they’re breastfeeding. So they can only use one hand.

These insights helped us to recognize that while there isn’t much of a problem for deep greens, there was a very real problem when it came to moms and other casual environmentalists. We had to provide tips that they could realistically implement in a judgment-free environment. And our interface needed to be more about clicking and less about typing.

We took the findings back to our client and they were amazed at the outcomes. And excited about the much bigger market opportunity ahead of them.

User Research Without Users

Now some of you may be thinking, “I could never do this. I can’t talk with users.”

Sometimes no matter what you do, you just can’t talk to any users. It happens to me too. I beg and I plead, but it just can’t happen for one reason or another.

But hope is not lost! There is a lot of deep knowledge about the user buried within your organization. It’s our job to tease it out.

There are a few key exercises I use to do that:

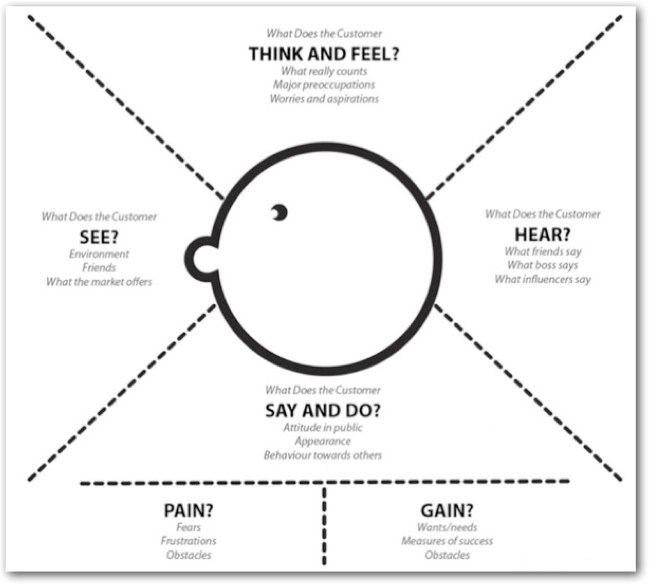

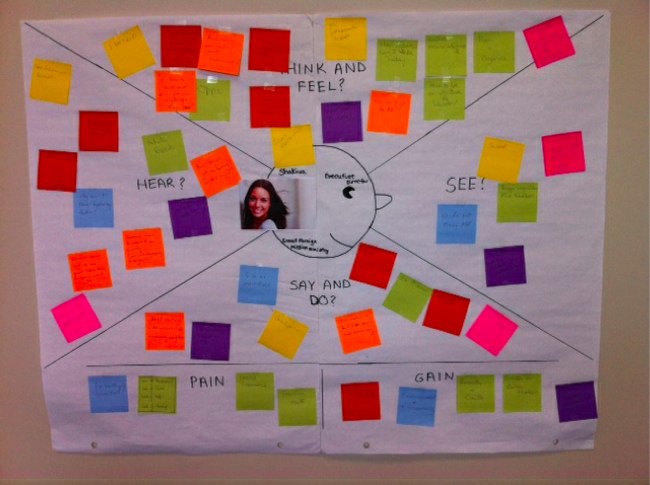

Empathy Map

The Empathy Map exercise was created by Dave Gray of XPLANE and is explained in detail in the book he co-authored titled, Gamestorming.

I get my teammates together in a room, and hopefully a few stakeholders join in too. We put a template of the empathy map up on the wall, and each person gets a stack of post-it notes. Then one at a time, we write a statement that we believe to be true about the user and put it in the appropriate quadrant. Slowly but surely, we start to create a picture of who this user is, by unearthing the intel we each hold about them.

As you take a step back, you’ll see a lot of statements that agree, and sometimes you’ll see a discrepancy. That gives you an opportunity to engage the group in a discussion about their assumptions and perspectives. Where did that information come from? Is it the result of an interaction with the customer that only a few people are privy to? Or is it a misconception that needs to be quashed now?

This technique allows you to pool your collective knowledge of the user and will give everyone who participates greater empathy for the people you serve.

5 Whys

Created by Sakichi Toyoda of Toyota Motor Corporation, 5 Whys is just what it sounds like. You state what you believe the user’s problem to be, and then like a 3-year-old, you keep asking Why. Five times. Each time you get closer to the real problem.

I’ve used this technique on projects where I wasn’t able to talk to an important segment of our users or to any users at all. Stakeholders told me what problem to solve and I was expected to solve it without any intel. Using 5 Whys lets me demonstrate that the problem they see is a symptom and not the root cause. It totally reshapes the conversation.

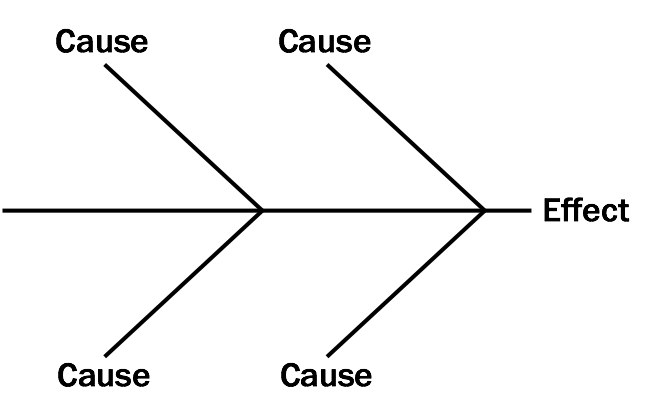

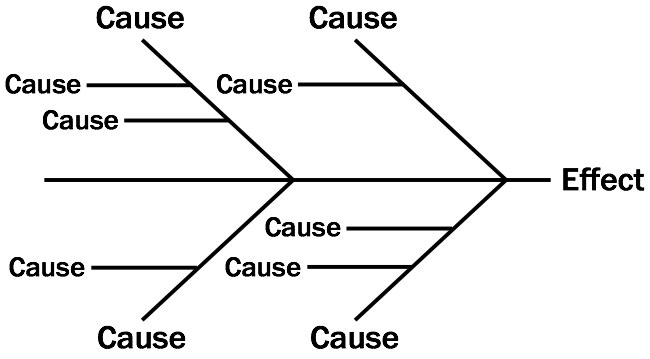

Fishbone Diagram

Exercises like these are how you find the truth. And the truth is what you design for. Just like 5 Whys, the Fishbone Diagram exercise is designed to get at the root cause of the problem you’re observing. First you put the problem you think you have (the effect) at the head of the fish. Then you ask, Why did this happen?, drawing a diagonal line for each cause of that effect. And from there you keep asking why, continuing to draw lines for the causes. Eventually you will no longer be able to ask why and you’ll know you’re at the root.

You have to be a bit obsessed sometimes to really get to the truth. This looks obsessive doesn’t it? It is. Because solving the real problem is the whole point.

That’s why my last principle of problem solving is:

Purpose: Be obsessed with the problem, not the solution

The root of the problem is hidden. Not everyone can see it. I consider it my job to see the problems that others don’t. That is the role I like to play.

An optimist says, “The glass is half full.” A pessimist says, “The glass is half empty.” A realist says, “Dudes, that glass is twice as big as it needs to be.”

I want to be the realist.

This is about seeing the underlying causes. Make the conversation about the root problem, not the symptoms. Assumptions are statements we take to be true without proof, and therefore we should limit them to the absolute minimum necessary.

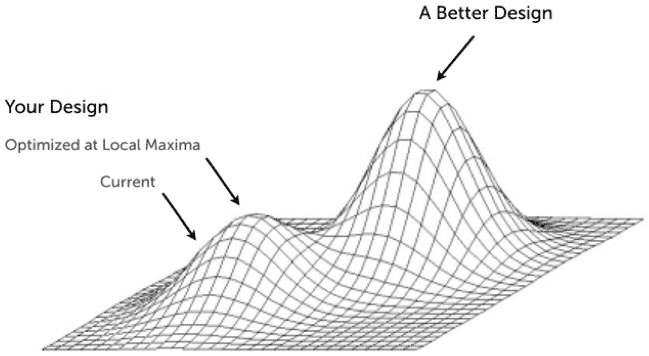

Josh Porter’s illustration of the local maxima problem makes this clear.

We often spend our time going from the current state to the peak state on the smaller problem. When we do as we’re told, we miss the bigger picture. I strive to be the one to see things more holistically, and helping others to see it too.

Crafting a problem statement can help you do that. It needs to be:

- Concise

- Specific

- Measurable

What is the problem or need? Who has the problem or need? Why is it important to solve? The work you’ve done getting to the root problem will help you fill in these blanks.

Who needs what because why.

This might look familiar to anyone who’s worked in an agile development setting. The purpose is similar, but here it’s being used on the grand scale.

You need to get this problem statement approved by your stakeholders before you spend a moment solving it. David Ogilvy, the legendary advertising executive and original Mad Man, wrote,

“I write out a definition of the problem and a statement of the purpose which I wish the campaign to achieve. Then I go no further until the statement and its principles have been accepted by the client.”

This was the problem statement we ultimately uncovered for Brighter Planet: Casual environmentalists need creative ways to conserve without the guilt trip because they have constraints on adapting their lifestyle.

Another format for communicating a problem statement is the 5Ws Technique, a popular journalist technique. Who? What? Where? When? Why? Answering these questions can achieve the same result.

However you choose to do it, make it an exercise in clear communication. Being a great designer, obsessing over the problem, means building these soft skills:

- Listening

- Empathy

- Connection

- Facilitation

- Persuasion

- Patience

This is what it takes to be a great communicator. That is what we all need to be. When you communicate the problem clearly and emphatically, you create believers. And ultimately you can end up having a major impact not only on how things are designed, but what gets designed in the first place.

That’s what happened to us with Brighter Planet. Our obsession with defining the problem changed the whole product.

We ended up creating a social network that allowed users to find new and creative ways to conserve, and share those actions with their friends. The carbon footprint calculator was broken out into several chunks so it could be completed gradually, and users would immediately see the impact of each response on their calculation. Every time users came to the site, they could refine their footprint a bit more by answering just one question. And questions were asked as multiple choice to allow for more clicking and less typing.

The work we put into defining the problem and defining the target audience completely transformed the product.

Now the first question I ask on every new project is, “How can I help you be more successful?”. I ask the stakeholder. I ask the customer. And I ask myself.

The persistence of the problem is purpose. So long as the problem exists, so does my purpose for working to solve it. So I have to ask: What’s your problem? What’s your purpose?

Life is too short to waste it solving the wrong problems. Make stuff that matters. To your organization. To your users. And to you.

Thank you for reading.

Further Reading

- Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems

- You Are Solving The Wrong Problem

- A New Make Mantra: A Statement of Design Intent

- 17 Types of Interviewing Questions

- My Best Advice to Conducting User Interviews

Related Posts:

- I did the UX design for Brighter Planet July 20, 2009 | 10 comments

- Customers First March 14, 2013 | 2 comments

- The truth about the presentation process February 21, 2013 | 6 comments

- Knowing Why Beats Knowing How August 6, 2012 | 13 comments

- Designing the Company, Not the Product August 15, 2012 | 4 comments

This is awesome. One of the best overviews I’ve ever read about what Design should accomplish and how to do it right. Congratulations!

Luis, that is amazing of you to say. Thank you so so much!

Currently stuck on a Design problem and needed something inspirational to clear the head – delighted I came across this! It’s amazing how sometimes even with design training you still need great blogs like this to reiterate the crucial points and focus you once again- thanks so much :) !

Marion, thrilled to hear this piece may have helped you in some way. That’s exactly why I do what I do. Hope you’ll keep reading!

Thanks for sharing all this!

Thank you for reading it, Alex!

Little heavy for me, but got insightful points.

Apologies if this was a bit dense, Gaurav. I realize a blog post might not have been the right medium for it. ebook?

Thank you for writing this article, it is great. I discovered many takeaways that I can apply to my work. I particularly appreciate how you emphasize the various ways to conduct user research. Very helpful!

Thank you so much, Sarah! I’m happy to hear that.

I’m always amazed at how much overlap I hear in our paths. I’ve just recently started to gain momentum with securing time and contacts for user research, and its made my work so much more purposeful.

In fact, it’s interesting to hear about your findings related to the “green” market. I had the opportunity this year to research the same audience, and was also surprised at the depth of some people’s commitment – catching shower water in buckets, etc.

As always, thanks for sharing!

Erin, it’s a shame we haven’t been able to connect more given how similar our philosophies are. I hope we can change that soon. Thank you for always being so supportive. I hope your summer is off to a great start!

What a refreshing read! You’ve eloquently captured many of the challenges I feel in my UX career with a large software company. Many, if not most, of the projects I’m assigned to are handed down the management chain without any clarity about the problems they are meant to solve…yet we jump into design anyway to satisfy schedules and internal stakeholders. Your article reminds me that there’s a better, “righter” way.

Keep fighting the good fight, Bret. Don’t let yourself be pushed down a path you don’t believe in. You have support out there!

Nice to see you using a cartoon from Throbgoblins — but not cited?

This last one might be more applicable to designing something useful:

http://www.marcrobertscartoons.com/cartoons_display/cartoon2207.jpg

I’m sorry Hank, I didn’t think I needed to cite the cartoon if the credits were already in the image.

Holy moly, thanks for writing this down. Much appreciated!

Thank you, Pim! You’re so welcome.

Really fantastic explanation of your process and the important insights behind it. This is immensely helpful to anyone trying to solve problems that matter. Thank you.

Thank you so much, River. That’s awesome to hear.

Whats your take on mental models? Do you find them helpful when you can’t get user participation on a project. Or when you are teeing up what to go after in discovery before you engage users? Seems like they are more commonly used with users first but was thinking may be a way to apply the technique with out them…

Love your stuff!

I love the mental model technique in theory. It’s immersive and effective. But most teams have nowhere near the amount of time to get it right. I tend to use much shorter, easy-to-achieve methods with my clients. They’re usually looking for quick insights over depth.

Dead on.

Woot!

This is great stuff! You never cease to capture people’s attention and hearts with your writing, Whitney.

Wow Christina, thank you!

Best article I’ve read in ages Whitney – it’s quite long but packed full of info and a fantastic advert for your talent. You know your stuff, no doubt!

Thank you so much, Mark! I really appreciate that.

I loved this talk at EdUI last year! I recently started reading Jonah Lehrer’s “Imagine” and was struck by the similarity of the Proctor and Gamble “Swiffer story” in both his book and your talk. I was under the impression that it was original research. Still, it’s a wonderful presentation and thank you for sharing it!

Thank you so much for the kind words, Shaun. I’m sorry if you felt mislead, I never intended to imply that I had done the research to discover the Swiffer story. It’s quite well-known. My source for the talk was actually the design agency’s website http://continuuminnovation.com/work/swiffer/ Hope this helps clear it up!

Great article. I have been training people on Problem Solving for decades now. The message in this article is bang on and simple enough for reader to appreciate. I loved it. I am sure author would not mind me sharing this link to all who I know.

Very much appreciated, please send far and wide.

Woow I like this article. Very informative – have really learned a lot of valuable tips and advice. Kudos!